Who are you guys?

We are both college professors at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Carl Bergstrom is a member of the Department of Biology, and Jevin West is a member of the Information School.

Is this your idea of a joke?

No. This is the website that accompanies a college course entitled "Calling Bullshit".

We taught the course as a one-credit, once-a-week lecture at the University of Washington during Spring Quarter 2017. Our course syllabus and readings, tools, and case studies are all available on this website. We recorded video of the lectures, and have made the edited videos available here. We expanded the class to a full three-credit course in Autumn 2017, taught it again in Autumn 2018, and plan to offer it annually during the autumn quarter.

Why are you doing this?

As we explain on our home page, we feel that the world has become over-saturated with bullshit and we're sick of it. However modest, this course is our attempt to fight back.

We have a civic motivation as well. It's not a matter of left- or right-wing ideology; both sides of the aisle have proven themselves facile at creating and spreading bullshit. Rather (and at the risk of grandiose language) adequate bullshit detection strikes us as essential to the survival of liberal democracy. Democracy has always relied on a critically-thinking electorate, but never has this been more important than in the current age of false news and international interference in the electoral process via propaganda disseminated over social media. Mark Galeotti's December 2016 editorial in The New York Times summarized America best defense against Russian "information warfare":

"Instead of trying to combat each leak directly, the United States government should teach the public to tell when they are being manipulated. Via schools and nongovernmental organizations and public service campaigns, Americans should be taught the basic skills necessary to be savvy media consumers, from how to fact-check news articles to how pictures can lie."

We could not agree more.

So is this some sort of swipe at the Trump administration?

No. We began developing this course in 2015 in response to our frustrations with the credulity of the scientific and popular presses in reporting research results. While the course may seem particularly timely today, we are not out to comment on the current political situation in the United States and around the world. Rather, we feel that in a democracy everyone will all be better off if people can see through the bullshit coming from all sides. You may not agree with us about the optimal size of government or the appropriate degree of US involvement in global affairs, and we're good with that. We simply want to help people of all political perspectives resist bullshit, because we are confident that together all of us can make better collective decisions if we know how to evaluate the information that comes our way.

What exactly is bullshit anyway?

Surprising as it may seem, there has been considerable scholarly discussion about this exact question. Unsurprisingly given that scholars like to discuss it, opinions differ.

As a first approximation, we subscribe to the following definition:

Bullshit is language, statistical figures, data graphics, and other forms of presentation intended to persuade by impressing and overwhelming a reader or listener, with a blatant disregard for truth and logical coherence.

It's an open question whether the term bullshit also refers to false claims that arise from innocent mistakes. Whether or not that usage is appropriate, we feel that the verb phrase calling bullshit definitely applies to falsehoods irrespective of the intentions of the author or speaker. Some of the examples treated in our case studies fall into this domain. Even if not bullshit sensu stricto, we can nonetheless call bullshit on them.

In this course, we focus on bullshit as it often appears in the natural and social sciences: in the form of misleading models and data that drive erroneous conclusions.

I'm a UW student. How can I take this course?

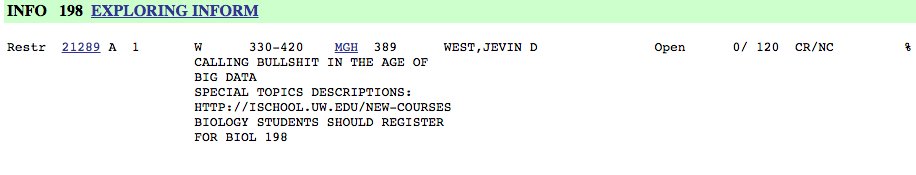

The course will next be offered in Autumn 2019 as a three-credit lecture, under the names INFO 270 and BIOL 270. For the latest information about the course, follow us on twitter, on facebook, or by joining our mailing list.

I'm not a UW student. Will the course be offered online?

Informally, yes. Our full syllabus is already online. You can find almost all of the readings on the internet and the few that are not online should be at your local library. We will be adding course materials, including new case studies and tools-and-tricks articles, as they become available. We have made video of the lectures freely available on youtube. For the latest updates on new material, follow us on twitter, on facebook, or by joining our mailing list.

In the longer-term we may develop an open online course (a MOOC). When and if we do so, we will endeavor to keep enrollment costs to an absolute minimum.

Can you actually use the word "bullshit" in the title of a college course?

Apparently yes.

Do you really need to use profanity to make your point? Isn't that rather puerile?

For better or for worse, the term bullshit has few exact synonyms in the English language. Horseshit is similar albeit with a somewhat more venomous connotation. In any case, this term is no more family-friendly. The best alternative we can think of is the shorter (and etymologically prior) bull.

One motivation for using the term bullshit is that this is the word employed when the subject is discussed in the philosophy literature. But let's be honest: we like the fact that the term is profane. After all, profane language can have a certain rhetorical force. "I wish to express my reservations about your claim" doesn't have the same impact as "I call bullshit!"

If you feel that the term bullsh*t is an impediment to your use of the website, we have developed a "sanitized" version of the site at callingbull.org. There we use the term "bull" instead of "bullsh*t" and avoid other profanity. Be aware, however, that some of the links go to papers that use the word bullsh*t or worse.

How could you have omitted Darrell Huff's 1954 book How to Lie with Statistics from your syllabus?

We acknowledge that Huff's book did a good job of providing a humorous and non-technical introduction to the perils of statistical reasoning to a 1950s audience. Unfortunately the casual racism and sexism of the illustrations make it virtually unusable as a college text today.

"Big data" is plural, you idiots.

That's not a question, but in any event we disagree. In common usage, the term "big data" refers to the use of, or field of study involving, very large data sets. Just as "Hydroponics has revolutionized the way we grow weed", "Big data has revolutionized the way we sell bullshit."

That said, we concede that the term big data may be problematic irrespective of whether treated as plural or singular. colleague Joel McLaughlin has pointed out that the adjective "big" indicates size, not number. To paraphrase his more eloquent explanation, if "big data" means copious data, then "big cats" must mean a shit-ton of cats.

Can you guys call bullshit on [this thing that I don't like]?

The purpose of this website is to teach people how to spot bullshit and refute it. We don't intend to use it as a platform for calling bullshit on things that we don't like, and we certainly don't intend to use it as a platform for calling bullshit on things you don't like.

Our case studies are not the most egregious examples of bullshit, nor the ones we most wish to debunk. Rather, they are chosen to serve a pedagogical purpose, drawing out particular pitfalls and highlighting appropriate strategies for responding. So read up, think carefully, and call bullshit yourself.

I'm an instructor. Can I teach this course at my institution or use your materials in my classroom?

Nothing would please us more. There are only so many students that we can reach first-hand, so we would be delighted to see others take up the cause. If you use the syllabus or materials, we have just two small requests.

Please acknowledge our efforts in your course materials. Mention our course and what you have drawn from it. Provide a link to our webpage (or callingbull.org if you prefer the sanitized version of the url). If you reproduce portions of our text, indicate the source. Basically, we just ask that you follow appropriate norms of academic attribution.

We would love to hear from you about how you are using these materials. Among other things, this helps us justify the time and effort that we are putting into the project. Any comments about what you find works well and what does not would also be most welcome.

Please do not make copies of our case studies, articles, or other web pages on your own web server. We view our course materials as works in progress and would like to keep a single version of record on our server that we can update over time. After all, should we ever discover that we've inadvertently spread bullshit, we want to be able to clean it up.

Doesn't your course just make matters worse by teaching people how to bullshit more effectively?

It is true that if one knows how to detect subtle bullshit, one can also create effective bullshit. As with biological weapons, there is no such thing as purely defensive bullshit research. And that puts us in a slightly awkward position Brandolini's Bullshit Asymmetry Principle. Brandolini's principle dictates that refuting bullshit requires an order of magnitude more effort than creating it. Unless one believes that good actors are an order of magnitude more common than bad actors, it might seem that teaching people more about the dark art of bullshit will only increase the amount of bullshit in the universe.

The problem with this line of reasoning is that it holds Brandolini's principle constant while changing the bullshit detection and bullshit creation abilities of the populace. We believe that as more people learn to detect and refute bullshit, Brandolini's ratio will change. Bullshit is easier to spread and harder to eliminate when people are not expecting it; it is also harder to eliminate when people don't know how to best refute it. This course should help on both accounts. In our more optimistic moments, we can even imagine a future in which the Second Law of Coprodynamics is violated.

What's with all the old art?

Bullshit is by no means a modern invention. Each page on this website features a famous bullshit artist of yore.

Here on this page, a detail from Michelangelo's 1512 Expulsion from the Garden. According to Christian theology, all of the pain and suffering (and mortality) that pervades human life can be traced to the lies that the serpent fed Eve about the fruit of knowledge.

On our syllabus page, Theodoor Rombouts's early 17th century The Denial of Saint Peter. At the Last Supper, Saint Peter assured Jesus that he would never deny him, but Jesus saw right through that. By the next morn, Saint Peter had lied three times in denial of the savior.

On the home page, Rafael's 1511 The School of Athens. Here Socrates is depicted as he obliterates the arguments of the Sophists, a group of purported scholars who constructed an entire philosophical school around talking bullshit. (Fortunately, the Sophists are long gone and no other school of philosophy would venture to lay its foundations on the same effluent base. )

On our contact page, Botticelli's 1494 Calumny of Apelles. King Midas looks down on a man falsely accused by figures representing Slander, Fraud, Ignorance, Suspicion, and Conspiracy.

On our about page, Nicholas Regnier's 1620 The Fortune Teller. One might imagine this fortune-teller makes her living through her ability to deceive the willing.

On our exercises page, Nicholas Poussin's 1654 Death of Sapphira. According to Acts 5 of the New Testament, Sapphira and her husband Ananias lied to Peter about holding back some of their money, and were struck dead for this. Nevermind that Peter himself earned a place on the header of our syllabus page for denying Jesus three times before the cock crowed.

On our lecture videos page, Dosso Dossi's 1524 Jupiter, Mercury, and Virtue . Mercury was the trickster of the Roman Dii Consentes.

Our case studies pages present many different renditions of a pioneering bullshit artist, Odysseus, and the foes he defeated . Not only does Odysseus best multiple foes through trickery and deceit; he is the original unreliable narrator. Here’s a leader who won a huge war and sacked a wealthy city, yet somehow managed to return home a decade later, impoverished and without any of his ships or men. The way he tells the tale, they were lost to unspeakable danger while he alone survived through his bravery, cunning, and heroism. Maybe the voyage really did go down the way he reports, but it sure is hard to verify given that no one survived to question his claims.

On our press coverage page, a detail from Piero di Cosimo's (1486-1510) The Death of Procris. This legends has been presented in many different forms by various authors, including Ovid in the Metamorphosis, but deception and misperception is a consistent theme. In one version of the tale, Cephalus tests the fidelity of his wife Procris by seducing her while in disguise. Later she has her own doubts about his loyalty, and follows him while he goes hunting. She mistakes his invocation of the wind as the name of a lover, leaps out from her hiding place, and is killed by his arrow when he mistakes her for a wild beast.

The header images on our tools and tricks pages offer tribute to those philosophers and scholars who over the centuries have sought to cut through the lies, ignorance, and superstition bring the light of knowledge to the world.